Total health care reform covering the Affordable Care Act (ACA), Medicare, Medicaid, the Children’s Health Insurance Program, the Federal Employees Health Benefits Program, and eventually, the Veterans Health Administration

The long-term vision is to provide an accessible and affordable nationally-guided quality health care system for everyone in the United States. The challenge is in how to reach this national health care vision and how to sustain it long into the future. It is going to take significant planning, preparation, and persistence to implement an effective comprehensive approach to achieve this vision. We’re not going to get there overnight and we need to approach this in a gradual, phased-in, step-by-step process.

The Affordable Care Act (ACA) is going to implode. ACA was rushed legislation ahead of a mid-term election cycle. It is over 2300 pages of an inefficient and ineffective legislation mess. It did provide insurance to many people who were previously uninsured, but with ineffective sustainability it rapidly became the Unaffordable Care Act. We need to take action to replace ACA as soon as we can. I have a comprehensive health care reform approach that takes incremental steps to gradually migrate the Affordable Care Act, Medicare, Medicaid, the Federal Employees Health Benefits Program, and eventually, the Veterans Health Administration into a unified nationally-guided health care system of private health care and health insurance providers covering all Americans.

The following section is an excerpt from an article by Joshua Holland on “The Nation” that accurately describes the current state our health care system and the challenges we face in moving forward with a national health care system. I apologize for the lengthy excerpt, but this is an enormous complex issue that requires extensive discussion to achieve an effective plan forward. You can scroll down to read the proposed approach based on the the following discussion.

Medicare-for-All Isn’t the Solution for Universal Health Care

Achieving universal coverage—good coverage, not just “access” to emergency-room care—is a winnable fight if we sweat the details in a serious way. If we don’t, we’re just setting ourselves up for failure. The health-care debate is moving to the left. But if progressives don’t start sweating the details, they’re going to fail yet again.

Within the broad Democratic coalition, it’s pretty clear that the discussion of health care has shifted to the left. Mainstream figures are embracing single-payer. Representative John Conyers’s Medicare-for-All bill currently has 115 Democratic co-sponsors in the House. And Senate minority leader Chuck Schumer recently said that single payer is now “on the table.” Assuming we have free and fair elections in the future, and Democrats regain power at some point, this is all very good news for single-payer advocates.

But that momentum is tempered by the fact that the activist left, which has a ton of energy at the moment, has for the most part failed to grapple with the difficulties of transitioning to a single-payer system. A common view is that since every other advanced country has a single-payer system, and the advantages of these schemes are pretty clear, the only real obstacles are a lack of imagination, or irresponsible Democrats and their donors. But the reality is more complicated.

For one thing, a near-consensus has developed around using Medicare to achieve single-payer health care, but Medicare isn’t a single-payer system in the sense that people usually think of it. This year, around a third of all enrollees purchased a private plan under the Medicare Advantage program. These private policies have grown in popularity every year, in part because the field has been tilted against the traditional, government-run program. Medicare Advantage plans must have a cap on out-of-pocket costs, for example, while the public program does not. Around one-in-four Medicare enrollees also purchase some sort of “Medigap” policy to cover out-of-pocket costs and stuff that the program doesn’t cover, and then there are both public and private prescription drug plans.

The array of options can be bewildering—it’s a far cry from the simplicity that single-payer systems promise.

At the same time, Medicare-for-All is really smart politics. Medicare is not only popular, it’s also familiar. Many of us have parents or grandparents who are enrolled in the program. And polls show that a significant majority of Americans now believe that it’s the government’s “responsibility to provide health coverage for all.”

But from a policy standpoint, Medicare-for-All is probably the hardest way to get there. In fact, a number of experts who tout the benefits of single-payer systems say that the Medicare-for-All proposals currently on the table may be virtually impossible to enact. The timing alone would cause serious shocks to the system. Conyers’s House bill would move almost everyone in the country into Medicare within a single year. We don’t know exactly what Bernie Sanders will propose in the Senate, but his 2013 “American Health Security Act” had a two-year transition period. Radically restructuring a sixth of the economy in such short order would be like trying to stop a cruise ship on a dime.

There has not yet been a detailed single-payer bill that’s laid out the transitional issues about how to get from here to there. We’ve never actually seen that. Even if you believe everything people say about the cost savings that would result, there are still so many detailed questions about how we should finance this, how we can deal with the shock to the system, and so on.

Centrist Democrats will no doubt be one obstacle to universal coverage, but a more fundamental problem is that compelling the entire population to move into Medicare, especially over a relatively short period of time, would invite a massive backlash.

The most important takeaway from recent efforts to reshape our health-care system is that “loss aversion” is probably the central force in health-care politics. That’s the well-established tendency of people to value something they have far more than they might value whatever they might gain if they give it up. This is one big reason that Democrats were shellacked after passing the Affordable Care Act (ACA) in 2010, and Republicans are now learning the hard way that this fear of loss cuts both ways.

Remember how much trouble President Obama got into when he said that if you like your insurance you can keep it? For something like 1.6 million people, that promise turned out to be hard to keep. And that created a firestorm. Those 1.6 million people represented less than 1 percent of the non-elderly population, and most of them lost substandard McPlans which left them vulnerable if they got sick. The ACA extended coverage to almost 10 times as many people, but those who lost their policies nonetheless became the centerpiece of the right’s assault on the law. Trump and other Republicans are still talking about these “victims” of Obamacare to this day.

Under the current Medicare-for-All proposals, we would be forcing over 70 percent of the adult population—including tens of millions of people who have decent coverage from their employer or their union, or the Veteran’s Administration, or the Federal Employees Health Benefits Program—to give up their current insurance for Medicare. Many employer-provided policies cover more than Medicare does, so a lot of people would objectively lose out in the deal.

Some large companies skip the middle man and self-insure their employees—and many offer strong benefits. We’d be killing that form of coverage. If we were to turn Medicare into a single-payer program, as some advocates envision, then we’d also be asking a third of all seniors to give up the heavily subsidized Medicare Advantage plans that they chose to purchase. Consider the political ramifications of that move alone. And because some doctors would decline to participate in a single-payer scheme, which would come with a pay cut for many of them under Medicare reimbursement rates, we couldn’t even promise that if you like your physician you can keep seeing him or her.

Don’t be lulled into complacency by polls purporting to show that single payer is popular—forcing people to move into a new system is all but guaranteed to result in tons of resistance. And that’s not even considering the inevitable attacks from a conservative message machine that turned a little bit of money for voluntary end-of-life counseling into “death panels.” Public opinion is dubious given that nobody’s talking about the difficulties inherent in making such a transition.

It’s true that every other developed country has a universal health-care system, and we should too. But make no mistake: Moving the United States to national health care would be unprecedented, simply because we spend more on this sector than any other country ever has.

For the most part, these countries were spending maybe 2 or 3 percent of their economic output on health care when they set up these systems after World War II. Most of them are spending 8 or 9 or maybe 10 percent of their output now, and this is 70 years later.

In 2015, the United States spent 17.8 percent of its output on health care. The highest share ever for an advanced country establishing a universal system was the 9.2 percent that Switzerland spent in 1996, and they set up an Obamacare-like system of heavily regulated and subsidized private insurance. (They also spend more on health care today than anyone but us.)

There’s a common perception that because single-payer systems cost so much less than ours, passing such a scheme here would bring our spending in line with what the rest of the developed world shells out. But while there would be some savings on administrative costs, this gets the causal relationship wrong. Everyone else established their systems when they weren’t spending a lot on health care, and then kept prices down through aggressive cost-controls.

Bringing costs down is a lot harder than starting low and keeping them from getting high. We do waste money on private insurance, but we also pay basically twice as much for everything. We pay twice as much to doctors. Would single-payer get our doctors to accept half as much in wages? It could, but they won’t go there without a fight. This is a very powerful group. We have 900,000 doctors, all of whom are in the top 2 percent, and many are in the top 1 percent. We pay about twice as much for prescription drugs as other countries. Medical equipment, the whole list. You could get those costs down, but that’s not done magically by saying we’re switching to single payer. You’re going to have fights with all of these powerful interest groups.

Single-payer advocates are mostly right about its benefits. These systems are simpler, they cut down on administrative costs, and they cover everyone. But the term “single-payer” is itself misleading. The truth is that many of the systems we refer to as single-payer are a lot more complicated than we tend to think they are. Canada, for example, finances basic health care through six provincial payers. Its Medicare system provides good, basic coverage, but around two in three Canadians purchase supplemental insurance because it doesn’t cover things like prescription drugs, dental health, or vision care. About 30 percent of all Canadian health care is financed through the private sector.

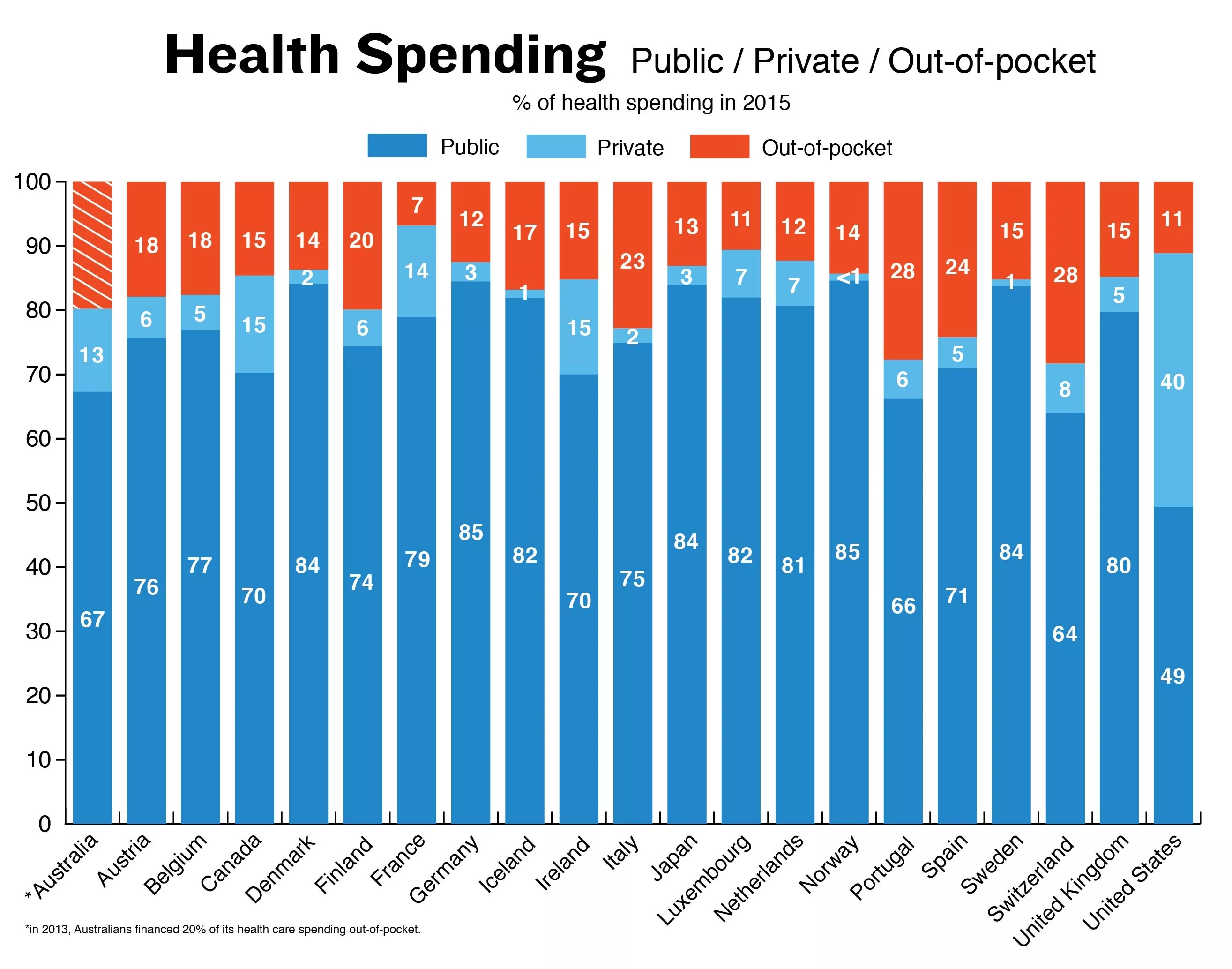

Most countries have mixed funding schemes that vary in complexity, and the term “single-payer” may be giving some people a false promise. Conyers’s Medicare-for-All bill promises to cover virtually everything while banishing out-of-pocket costs, but no other health-care system offers such expansive benefits. Even people living in Scandinavian social democracies face out-of-pocket expenses: In 2015, the most recent year for OECD data, the Swedes covered 15 percent of their health costs out-of-pocket; in Norway, it was 14 percent and the Finns shelled out 20 percent out-of-pocket.

Most countries with “single-payer” systems rely on some combination of public insurance, various mixes of mandatory and voluntary private insurance (usually tightly regulated), and out-of-pocket expenditures (often with a cap). They offer free coverage for those who can’t afford it, but the exact benefits vary from country-to-country.

Germany’s “single-payer” system has 124 not-for-profit insurers participating in one national exchange. About 10 percent of Germans—the wealthiest ones—opt out of the national system and go fully private, and most of them buy plans from for-profit insurers.

The Dutch system is somewhat like Obamacare in that everyone must purchase insurance for basic services from private insurers. But the similarities end there: Insurers are barred from distributing profits to their shareholders, and a separate, entirely public scheme covers long-term care and other costly services. Premiums are subsidized, but most Dutch people purchase supplemental insurance to cover things like dental care, alternative medicine, contraceptives, and their co-payments.

The French system is often cited as the best in the world, and about a quarter of it is financed through the private sector. The French are mostly covered through nonprofit insurers in a single national pool, but most working people get their policies through their employers. Almost all French citizens either purchase government vouchers to cover things like vision and dental care, or are provided with them at no cost if necessary. The system is financed through a complicated mix of general revenues, employer contributions, payroll taxes and taxes on drugs, tobacco, and alcohol.

So the United States isn’t unique because it uses a mix of public and private financing—the big difference, as these OECD data show, is that we rely much more heavily on private insurance than any other wealthy country.

Understanding that other countries’ schemes vary significantly in the details—and that in the United States, the cost of care would remain a serious challenge under any system—should lead to a different conversation among progressives. Rather than making Medicare-for-All a litmus test, we should start from the broader principle that comprehensive health care is a human right that should be guaranteed by the government—make that the litmus test—and then have an open debate about how best to get there. Maybe Medicaid is a better vehicle. Perhaps a long phase-in period to Medicare-for-All might help minimize the inevitable shocks. There are lots of ways to skin this cat.

An obvious alternative to moving everyone into Medicare is to simply open up the program and allow individuals and employers to buy into it. We could then subsidize the premiums on a sliding scale. But recent experience with the ACA suggests that this kind of voluntary buy-in won’t cover everyone, or spread out the risk over the entire population.

In other countries, you’re basically guaranteed coverage and then they figure out how to pay for it. Some of that money may come from you, some will come from your employer and some of it will come from general funds. We don’t have that approach. People who don’t have coverage from their employers have to figure out how to sign up—either for Medicaid, or through the exchanges. Yes, we had a penalty to encourage people to do that, but they still have to navigate this incredibly complex system.

Maybe there’s a better way still that hasn’t yet been discussed. The fight for a universal health-care system in the United States is now in its 105th year, and if we don’t admit that financing any kind of universal system is going to be especially difficult given how much we spend, or acknowledge the role that loss aversion plays in the politics of reform, then we’re going to fail again the next time we get a shot at it.

Anyone who tells you that the most expensive health care system in the world is going to undergo a sudden shift to highly efficient and low-price medicine has not been studying American medicine.

Choosing the best approach moving forward

Few countries have national single-payer health care systems. The national single-payer health care systems in existence today provide basic health care and reduce administrative costs, but they are significantly wanting in anything beyond that. It is analogous to “universal transportation” where everyone gets a automobile, but that automobile is a Yugo. I don’t know about you, but I definitely prefer my Toyota Tacoma.

The single-payer health care systems that fare better are those of the Nordic model. In the Nordic model of Finland, Sweden, and Denmark, the health care system is single-payer, but it is not national, it is municipal. The municipalities collect the money, the taxes to fund health care locally, and the money is spent locally. This would be somewhat equivalent to a single-payer health care system where the states collect the taxes to fund health care in their states and spend the money in their states.

The national health care systems that provide the highest quality health care and have faster access to specialists than the US health care system are those nationally-guided private provider health care systems of the Netherlands, Germany, and Switzerland. The nationally-guided private insurance provider systems benefit from the competition between service providers in driving excellence of the health service available to their citizens. Of those three countries over the past decade, the Dutch health care system is repeatedly ranked as the best in Europe.

Where to start in the US

After reviewing the ACA framework in the over 2300 page bill, it would take less effort to start from scratch instead of trying to revise the ACA legislation. Of other US health care services, the Federal Employees Health Benefits Program (FEHB) provides the best framework to serve as the basis for a unified national health care system to cover everyone in the US.

The FEHB is a system of “managed competition” through which employee health benefits are provided to federal government employees, retirees and their survivors. Competition drives excellence. The government contributes 72% of the weighted average premium of all plans, not to exceed 75% of the premium for any one plan.

The FEHB program allows some insurance companies, employee associations, and labor unions to market health insurance plans to governmental employees. The program is administered by the United States Office of Personnel Management (OPM). There are over 200 plans participating in the FEHB program with about 20 plans that are nationwide or almost nationwide. The remaining locally available plans are almost all HMOs. It enrolls about eight million persons in total. While its enrollment is about one-fifth that of the nation’s largest health insurance program, Medicare, it spends less than one-tenth as much because most enrollees are below age 65 and cost far less on average than the elderly and disabled who constitute Medicare’s enrollees.

The FEHB program relies on consumer choices among competing private plans to determine costs, premiums, benefits, and service. This model is in sharp contrast to that used by original Medicare. In Medicare, premiums, benefits, and payment rates are all centrally determined by law or regulation (there is no bargaining and no reliance on volume discounts in original Medicare; these parameters are set by fiat). Over time, the FEHB program has outperformed original Medicare not only in cost control, but also in benefit improvement, enrollee service, fraud prevention, and avoidance of “pork barrel” spending and earmarks. (Medicare Part D has also controlled costs far better than originally forecast through a competitive, consumer-driven system of plan choices similar to and modeled after the FEHB program.)

One of the most prominent features of the FEHB program is the choices it allows. There are three broad types of plans: fee-for-service and preferred provider organization (PPO), usually offered in combination; HMOs; and high-deductible health plans and other consumer-driven plans. In the FEHB program the federal government sets minimal standards that, if met by an insurance company, allows it to participate in the program. The result is numerous competing insurance plans that are available to federal employees.

The underlying legislation for the FEHB program is minimal and remarkably stable, particularly in comparison to Medicare. The FEHB statute is only a few dozen pages long, and only a few paragraphs are devoted to the structure and functioning of the program. Regulations are minimal; only another few dozen pages. In contrast, the Medicare statute found in title 18 of the Social Security Act is about 400 pages long and the accompanying regulations consume thousands of pages in the U.S. Code of Federal Regulations.

The FEHB program has often been proposed as a model for national health insurance and sometimes as a program that could directly enroll the uninsured. Notable economist Alain Enthoven explicitly built a proposal for a system of “managed competition” as a national health reform decades ago, and has continued promoting the idea ever since. A version of this proposal was adopted by the Netherlands in their national health care reform in 2006. Ever since that major reform of their health care system, the Dutch system repeatedly maintains its number one position at the top of the annual Euro health consumer index each year. The Netherlands was also ranked first in a study comparing the health care systems of the United States, Australia, Canada, Germany and New Zealand.

According to the Health Consumer Powerhouse, the Netherlands has ‘a chaos system’, meaning patients have a great degree of freedom from where to buy their health insurance, to where they get their healthcare service. But the difference between the Netherlands and other countries is that the chaos is managed. Healthcare decisions are being made in a dialogue between the patients and healthcare professionals.

The proposed solution for an accessible and affordable national health care system

One of the prominent proposals for health reform in the United States, the proposed bipartisan Healthy Americans Act (HAA) in 2007 and 2009, was largely modeled after the FEHB program, as were recent “Republican Alternative” proposals by Representative Paul Ryan.

Senator Daniel Inouye was a co-sponsor of the Healthy Americans Act (HAA) bill in both 2007 and 2009. The HAA is a Senate bill that had proposed to improve health care in the United States, with changes that included the establishment of universal health care. It would transition away from employer-provided health insurance, to employer-subsidized insurance, having instead individuals choose their health care plan from state-approved private insurers. It sought to make the cost of health insurance more transparent to consumers, with the expectation being that this would increase market pressures to drive health insurance costs down. The proposal created a system that would be paid for by both public and private contributions. It would establish Healthy Americans Private Insurance Plans (HAPIs) and require those who do not already have health insurance coverage, and who do not oppose health insurance on religious grounds, to enroll themselves and their children in a HAPI. According to its sponsors, it would guarantee universal, affordable, comprehensive, portable, high-quality, private health coverage that is as good or better than Members of Congress had at that time. A 2008 preliminary analysis by the Congressional Budget Office concluded it would be “essentially” self-financing in the first year that it was fully implemented.

The HAA made employer-provided insurance portable by converting the current tax exclusion for health benefits into a tax deduction for individuals. The HAA provided for the establishment or identification of a “State Health Help Agency” in each U.S. state government which would administer the HAPI plans in each state, help its citizens evaluate the options available, oversee enrollment, and help with the transition from Medicaid and CHIP, among other responsibilities. Under HAA the Federal Employees Health Benefits Program and State Children’s Health Insurance Program would be replaced and Medicaid participants are transitioned out of that program.

Seven goals for health care reform reflected in HAA include:

- Ensure that all Americans have health care coverage;

- Make sure health care coverage is affordable and portable;

- Implement strong private insurance market reforms;

- Modernize federal tax rules for health coverage;

- Promote improved disease prevention and wellness activities, as well as better management of chronic illnesses;

- Make health care prices and choices more transparent so that consumers and providers can make the best choices for their health and health care dollars; and

- Improve the quality and value of health care services.

HAA was characterized as “harnessing the Democratic desire to get everyone covered to the Republican interest in markets and consumer choice.”

In my proposed solution, I go further in expanding the scope of the HAA to eventually include Medicare and Veterans Health Administration recipients. The funding sources for the Medicare and Veterans Health Administration recipients would initially remain unchanged to cover the health care services through HAA after the transition. Under this streamlined, unified nationally-guided health care system we will realize improved health care with cost containment resulting from increases in efficiency, effectiveness, and national participation.

By sweating the details, we can achieve this vision of an affordable, accessible, and sustainable unified nationally-guided health care system for everyone in the United States.